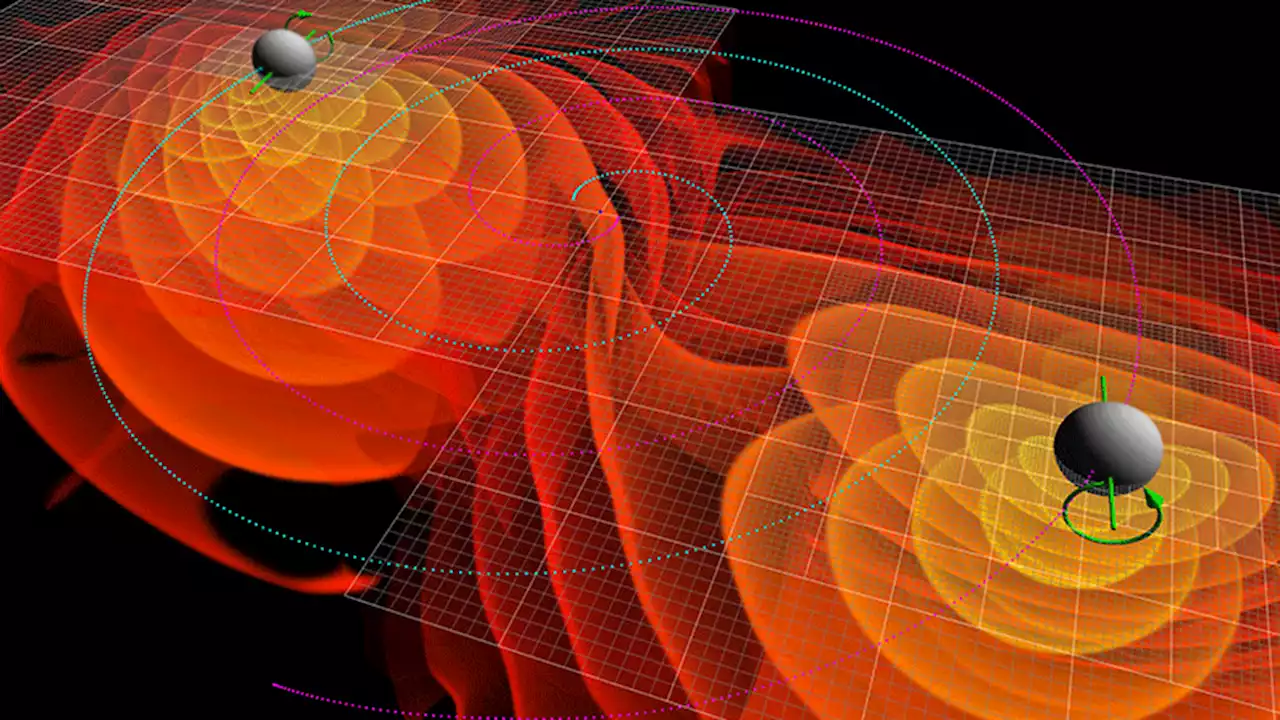

The black holes found each other late in life before colliding.

“This is actually the nice thing about this type of analysis,” says LIGO scientific collaboration spokesperson Patrick Brady, a physicist at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee who was not affiliated with the new study. “We deliver the data in a format that can be used by other people and then [they] will have access to try out new techniques.”

To compile so many new signals in data that had already been gone over by other researchers, Olsen’s group lowered the analytical bar a little. “Out of the 10 new ones,” Olsen says, “there are about three of them, statistically, that probably come from noise,” rather than being definitive black hole merger detections. Assuming that the merger of black holes strangers is not among the errant signals, it almost certainly tells a tale of black hole histories distinct from the others seen so far.

“It would be [extremely] unlikely for this to come from two black holes that have been together for their whole lifespan,” Olsen says. “This must have been a capture. That’s cool because we’re finally able to start probing that region of the [black hole] population.” Brady notes that “we don’t understand the theory [of black hole mergers] well enough to be able to confidently predict all of these types of things.” But the recent study may point to new and interesting opportunities in gravitational wave astronomy. “Let’s follow this clue to see if it really is reflecting something rare,” he says. “Or if not, well, we’ll learn other things.”