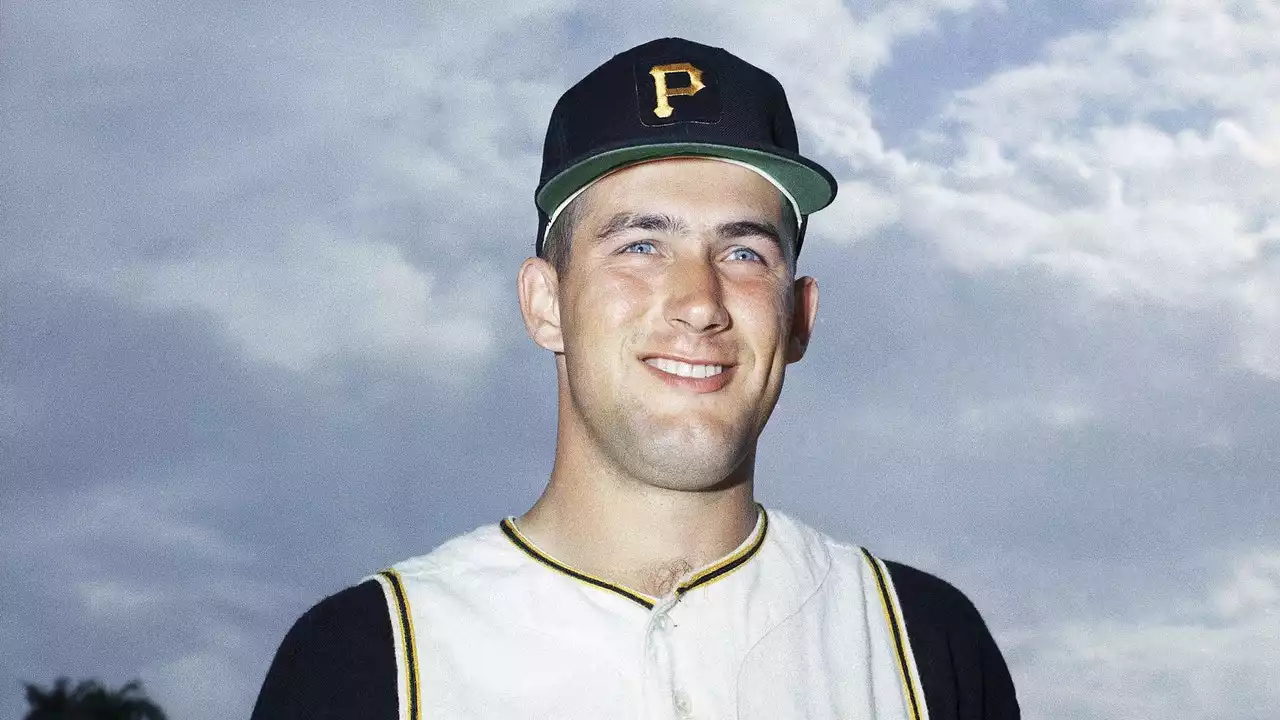

From 1975: Roger Angell on the Pirates’ star pitcher Steve Blass, who retired at 33 owing to two years of mysterious pitching—a sudden, near-total inability to throw strikes. NewYorkerArchive

The photograph shows a perfectly arrested moment of joy. On one side—the left, as you look at the picture—the catcher is running toward the camera at full speed, with his upraised arms spread wide. His body is tilting toward the center of the picture, his mask is held in his right hand, his big glove is still on his left hand, and his mouth is open in a gigantic shout of pleasure.

The summer of 1972—the year after his splendid World Series—was in most respects the best season that Steve Blass ever had. He won nineteen games for the Pirates and lost only eight, posting an earned-run average of 2.48—sixth-best in the National League—and being selected for the N.L. All-Star team. What pleased him most that year was his consistency.

Then it was over. The winning White Sox and the losing Orioles exchanged cheers, and Karen Blass, a winning and clearly undefeated mother, came over and introduced me to the winning catcher and the winning second baseman.

The Pittsburgh organization signed Steve Blass right out of Housatonic High in 1960, and he began moving up through the minors. He and Karen Lamb were married in the fall of 1963, and they went to the Dominican Republic that winter, where Steve played for the Cibaeñas Eagles and began working on a slider. He didn’t quite make the big club when training ended in the spring, and was sent down to the Pirates’ Triple A club in Columbus, but the call came three weeks later.

He lit a cigar and blew out a little smoke. “You know, this thing that’s happened has been painted so bad, so tragic,” he said. “Well, I don’t go along with that. I know what I’ve done in baseball, and I give myself all the credit in the world for it. I’m not bitter about this. I’ve had the greatest moments a person could ever want. When I was a boy, I used to make up those fictitious games where I was always pitching in the bottom of the ninth in the World Series. Well, I reallyit.

Strikeouts are of no particular use in defining pitching effectiveness, since there are other, less vivid ways of retiring batters, but bases on balls matter. To put it in simple terms, a good, middling pitcher should not surrender more than three or four walks per game—unless he is also striking out batters in considerable clusters. Last year, Ferguson Jenkins, of the Texas Rangers, gave up only forty-five walks in three hundred and twenty-eight innings pitched, or an average of 1.19 per game.

“It was the worst experience of my baseball life,” Blass told me. “I don’t think I’ll ever forget it. I was embarrassed and disgusted. I was totally unnerved. You can’t imagine the feeling that you suddenly have nowhat you’re doing out there. You have no business being there, performing that way as a major-league pitcher. It was kind of scary.”

The Mets game was his last of the year. His statistics for the 1973 season were three wins and nine defeats, and an earned-run average of 9.81. That figure and his record of eighty-four walks in eighty-nine innings pitched were the worst in the National League.I went to another ballgame with Steve Blass on the night after the Little League affair—this time at Three Rivers Stadium, where the Pirates were meeting the Cardinals.

For the final three innings of the game, Blass and I moved upstairs to general manager Joe Brown’s box. Steve was startled by the unfamiliar view. “Hey, you can really see how itfrom here, can’t you?” he said. “Down there, you’ve got to look at it all in pieces. No wonder it’s so hard to play this game right.”still makes me wince a little.” It was a moment or two before I realized that Robinson was wearing Blass’s old uniform number. Robinson fanned, and Blass said, “Same old twenty-eight.

The training period made it clear that nothing had altered with him , and when the club went North he was left in Bradenton for further work. He joined the team in Chicago on April 16th, and entered a game against the Cubs the next afternoon, taking over in the fourth inning, with the Pirates down by 10–4. He pitched five innings, and gave up eight runs , five hits, and seven bases on balls.

In truth, nothing helped. Blass knew that his case was desperate. He was almost alone now with his problem—a baseball castaway—and he had reached the point where he was willing to try practically anything. Under the guidance of pitching coach Don Osborn, he attempted some unusual experiments. He tried pitching from the outfield, with the sweeping motion of a fielder making a long peg. He tried pitching while kneeling on the mound.

Most painful of all, perhaps, was the fact that the men who most sympathized with his incurable professional difficulties were least able to help. The Pirates were again engaged in a close and exhausting pennant race fought out over the last six weeks of the season; they moved into first place for good only two days before the end, won their half-pennant, and then were eliminated by the Dodgers in a four-game championship playoff.

Steve Blass stayed home last winter. He tried not to think much about baseball, and he didn’t work on his pitching. He and Karen had agreed that the family would go back to Bradenton for spring training, and that he would give it one more try. One day in January, he went over to the field house at the University of Pittsburgh and joined some other Pirates there for a workout. He threw well.

Three days later, the Pirates held a press conference to announce that they had requested waivers from the other National League clubs, with the purpose of giving Blass his unconditional release. Blass flew out to California to see Dr. Bill Harrison once more, and also to visit a hypnotist, Arthur Ellen, who has worked with several major-league players, and has apparently helped some of them, including Dodger pitcher Don Sutton, remarkably.

Blass once told me that there were “at least seventeen” theories about the reason for his failure. A few of them are bromides: He was too nice a guy. He became smug and was no longer hungry. He lost the will to win. His pitching motion, so jittery and unclassical, at last let him down for good. His eyesight went bad. The other, more serious theories are sometimes presented alone, sometimes in conjunction with others. Answers here become more gingerly.

Dave Giusti : “Steve has the perfect build for a pitcher—lean and strong. He is remarkably open to all kinds of people, but I think he has closed his mind to his inner self. There are central areas you can’t infringe on with him. There is no doubt that during the past two years he didn’t react to a bad performance the way he used to, and you have to wonder why he couldn’t apply his competitiveness to his problem.

I ventured to repeat Nellie King’s guesses about the mystery to Steve Blass and asked him what he thought. “That’s pretty heavy,” he said after a moment. “I guess I don’t have a tendency to go into things in much depth. I’m a surface reactor. I tend to take things not too seriously. I really think that’s one of the things that’s“There’s one possibility nobody has brought up,” he said. “I don’t think anybody’s ever said that maybe I just lost my control.

Brasil Últimas Notícias, Brasil Manchetes

Similar News:Você também pode ler notícias semelhantes a esta que coletamos de outras fontes de notícias.

Promotional video leaks for the most exciting and ambitious Motorola phone since the DROIDA promotional video for the Motorola Edge 30 Ultra is leaked by Evan Blass showing off the design of Motorola's highly anticipated new flagship.

Promotional video leaks for the most exciting and ambitious Motorola phone since the DROIDA promotional video for the Motorola Edge 30 Ultra is leaked by Evan Blass showing off the design of Motorola's highly anticipated new flagship.

Consulte Mais informação »

Wolves legend Steve Daley urges prostate cancer checksSteve Daley said he thought he was 'invincible' until he was diagnosed with the disease.

Wolves legend Steve Daley urges prostate cancer checksSteve Daley said he thought he was 'invincible' until he was diagnosed with the disease.

Consulte Mais informação »

How to manage your money when the stock market dropsConsumer prices are quickly rising and recession fears are on the mind. Before you consider selling or making any hasty trades, watch this video for tips on managing your money when the market drops.

How to manage your money when the stock market dropsConsumer prices are quickly rising and recession fears are on the mind. Before you consider selling or making any hasty trades, watch this video for tips on managing your money when the market drops.

Consulte Mais informação »

For Mary Peltola, a sudden shift to national spotlight after winning Alaska’s special U.S. House electionThe Democrat, who won the special election to serve the last months of the late Rep. Don Young’s term, has seen a surge of national attention as she prepares to take office and campaigns for the November general election.

For Mary Peltola, a sudden shift to national spotlight after winning Alaska’s special U.S. House electionThe Democrat, who won the special election to serve the last months of the late Rep. Don Young’s term, has seen a surge of national attention as she prepares to take office and campaigns for the November general election.

Consulte Mais informação »

Steve Harvey-backed company adds jobs in tech worldSteve Harvey is a founding partner of Gamestar+, which will create more than 100 game development jobs in the U.S. as part of its recent acquisition of Mighty Kingdom.

Steve Harvey-backed company adds jobs in tech worldSteve Harvey is a founding partner of Gamestar+, which will create more than 100 game development jobs in the U.S. as part of its recent acquisition of Mighty Kingdom.

Consulte Mais informação »